Recultivate

Recultivate

An exploration in the preservation of Indigenous plants through considered biophilic design. Featuring Tait’s new planting & seating collection, Xylem, by leading Australian designer Adam Goodrum.

Many of Victoria’s Indigenous ecological sites are rapidly becoming vulnerable due to industrialised agriculture and urbanisation. Recultivate seeks to spread ideas around the importance of preserving these grasslands, shrublands and wetlands, and how considered biophilic design may assist in sustaining these indispensable plants and ecosystems. Recultivate illustrates a vital conduit between people and plants.

Produced in partnership with Victorian Indigenous Nurseries Co-op (VINC), TERRAIN and Collingwood Yards.

This installation is part of Melbourne Design Week 2022, an initiative of the Victorian Government in collaboration with the NGV.

Meet the team behind Recultivate

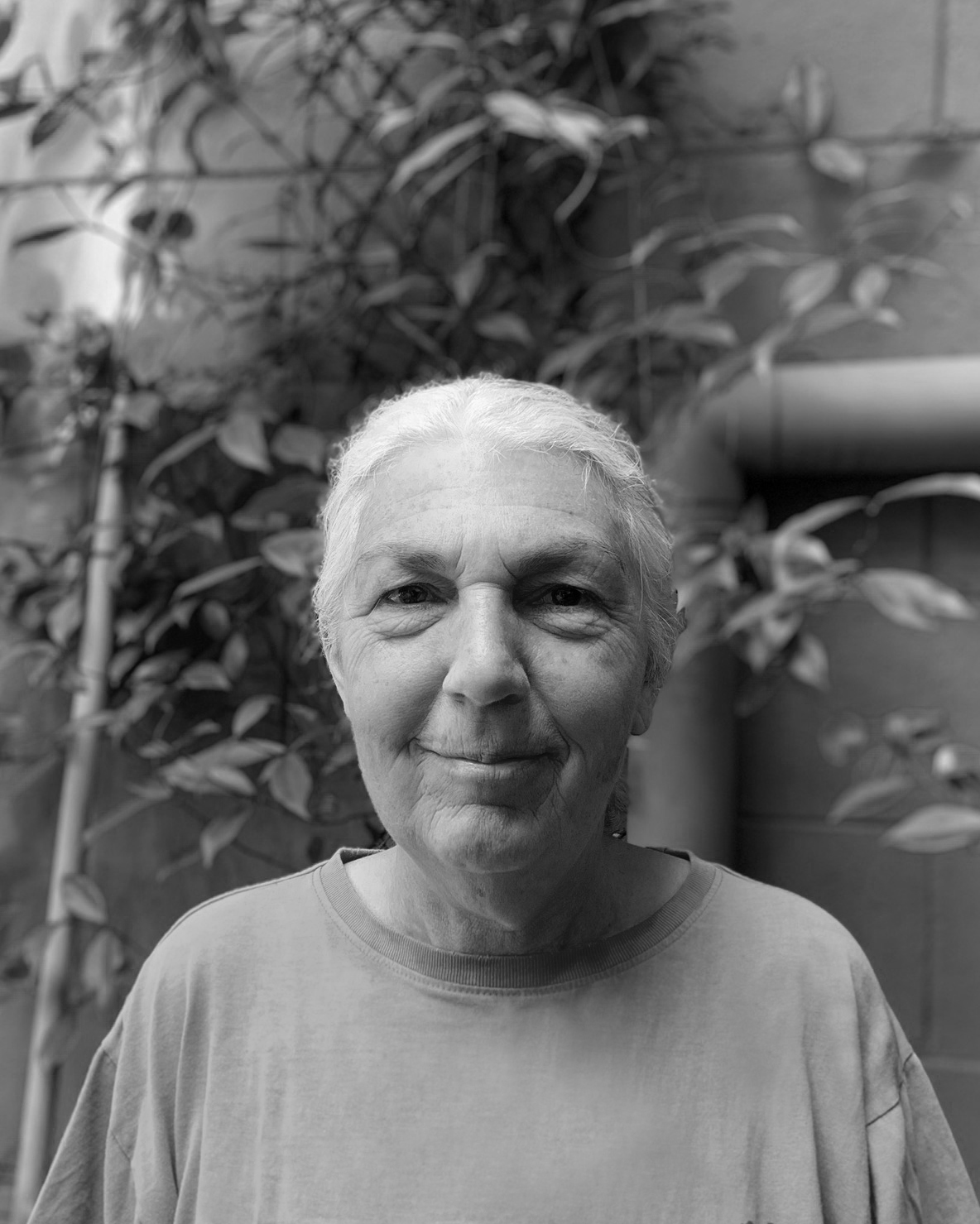

Cristina Napoleone,

Director of TERRAIN

TERRAIN create playful physical and digital spaces to remind humans that we are embedded in a more-than-human-world.

Below we hear from Cristina on what it means to ‘Recultivate’, and explore the facets concerning our interdependence with nature.

Introduction

My name is Cristina Napoleone and I’m the director of TERRAIN Projects.

When Tait got in touch with us to join this project for Melbourne Design Week that features their new Xylem collection by leading Australian designer, Adam Goodrum, it was clear that the vision Tait could see ahead required a deeper level of exploration for what it means to preserve the landscapes that their pieces rely on through considered design. TERRAIN’s key involvement with the project was in consulting with Tait directly, and sharing how they might calibrate their work and this project toward a more robust perspective on sustainability.

As a brief introduction, I founded TERRAIN in February 2020, as an initiative that creates playful physical and digital spaces to remind humans that we are embedded in a more-than-human world. The project emerged as a result of a deep questioning, curiosity and enquiry through studies of integrative geography – asking centrally how our society has found itself in this persistent ecological crisis we currently face, and why it feels as though we’re still not doing what needs to be done at the pace required. It became clear that even with the most highly advanced technologies and engineering feats to address our many facets of our over-consumption and short-termism, their longevity will inevitably be undermined by the worldview that persists and saturates our society, that of human-nature separation. It is therefore TERRAIN’s mission to unravel these binaries we have walled up around ourselves as human beings, to reveal the world as it truly exists and to allow space for us to remember what it feels like to live in such a way.

TERRAIN emerged and operates primarily on the unceded land of the Wurundjeri Woi Wurrung people of the Eastern Kulin Nations. I acknowledge and pay respect to their elders past, present and emerging, to their wisdom, culture and lands that continually remind me of what it means to be human. I also recognise that today we are in relationship with many lands all at once too as I record this audio remotely from Northern California. Our emerging digital territories of the internet rely on infrastructures that include millions of data servers, satellites in space, and cables that run through the deep sea – touching aspects of this planet far beyond the physical reach of my two feet.

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people have been living harmoniously with Country for over 60,000 years, as the oldest living culture on Earth. TERRAIN’s mission dedicates itself to the continual unlearning of colonial ways and harmful worldviews as we listen and learn from our Indigenous teachers and elders on how we are to live in harmony with all land, waters, air, space, and seas – and with all of the inhabitants to which we share them with.

At TERRAIN, part of the services we offer are environmental and creative consultancy. We felt that in offering such services, we can strategically widen this works impact and uptake across the cultural landscape in a very practical sense. When Tait approached us, they were attracted to our vision and mission, coupled with a curiosity as to how it could be integrated into their new Xylem collection and their business more broadly.

As you might imagine, we do sustainability consulting a little differently as it has emerged from a robust view of sustainability rather than a short-termist quick fix. Narrative is a powerful force in all aspects of life, and is particularly relevant today for the projects being materialised at a rapid rate. I passionately believe coupled with some technologies, the real transitions we need in our world require finding ways to creatively align, re-calibrate and prepare pre-existing industries for the future that’s already here. This is why in addition to revitalising practical operations to lighten their impact on our planet and shift toward regenerative solutions, we also focus our attention holistically on the underlying story that is being perpetuated. If we can work together in partnership with everyday businesses and organisations, a more-than-human ethics rollout and normalisation within culture can be motivated with a far wider-reaching impact, at the pace required to tackle the complex challenges of our times.

A Daily Practice

Over to the story of Recultivate, first I pause here to ask what’s in the name. To re – ‘cultivate’, we are reminded of what it means to try and acquire or develop a quality, sentiment or skill with attentiveness. To return.

If you are presently in the Collingwood Yards courtyard with the installation, or otherwise elsewhere as you listen to these words – I invite you now to sit or stand in a comfortable position with your feet planted firmly with the ground that meets you. Take a look around, what do you see? Look around for some native grasses, those in the planters or elsewhere around you. Once your attention has been held by one of these agents, take a moment to find some familiarity. Quieten yourself and let go of what is not here. Be present in this moment as you observe the gentle weep of the grasses, their lightness as they dance in continual motion with air. Let go of any expectation or preconceived notions of what you think this plant is, the name, the taxonomy, the science – let your imagination decide what this grass is called, what it likes, how it might sense you or receive this encounter. You may find your mind beginning to form questions for each stem and culm. Each question is completely valid, allowing your curious mind to take over each encounter rather than your critical mind halting this process from unfurling in its tracks. Some questions might seem silly or obvious but this doesn’t matter. What are your roots doing? Are you cold? What does it feel like to be here? You’ve now begun to form a relationship, the very beginning. Make a clear effort to return to this same place several times over the coming week, and months – as often as you can. Try to spend a minimum of 15 minutes each time quietly contemplating, and free from distractions. You’d be surprised with what you can learn, and the knowledge and wisdom that might be shared with you. The Earth is calling us back, all we are required to do is be quiet and listen. Use this as a daily practice, and increase the intervals of time when you’re ready. In our lives we have complicated almost everything, even the very beginnings of how to build a relationship with another. To ask questions, to not be self-centred. There is a deep sense of renewal that emerges when we simplify that which does not wish to be overly-complicated. When feeling stress, overwhelm, tiredness – return to this place, and sit and observe quietly to the worlds that simultaneously coexist outside of yourself. Here you will find stillness, and quiet. Recultivate this attentiveness. It may take some practice, like riding a bicycle, but with time you’ll align yourself back to the more-than-human world to which you belong and is calling you back.

As our native grasslands and indigenous plants are becoming increasingly vulnerable from industrialised agriculture and urbanisation, our chances of everyday encounters also diminish. Refamiliarising and rebuilding our relationship with these key agents of our home landscape is central to their welcomed return and flourishing.

Tait has begun here with designing these agents into our built spaces, which is one way of remembering this forgotten relationship, and being reminded – especially in spaces designed for contemplation, of the place that we are in. Designing with nature very practically heals our native ecosystems in urban spaces too, by allowing a mutual flourishing of non-human life with native bees birds and other fauna being welcomed back into these landscapes as cohabitants and mutual residents. Continue to cultivate a daily practice and perception of these elements, as you sit outside in the morning when the air is silent, or at the end of the day to calm the buzz and slow back down.

The Story of the Kangaroo Grass Seed

Planted within the installation is Kangaroo Grass (also known as Themeda triandra). Draw your attention to the seed head, to beginnings. To understand our place and role in the world when many of our human intelligences appear to be showing their cracks and deep flaws, let us turn to the intelligences of our more-than-human world, to what seed intelligences are offering to teach us, but first we must attune to this wisdom.

Salmon Creek Farm located in Northern California say that: “a garden that values only living plants is a denial of reality. The story of a plant continues long after moisture stops coursing through its roots, stems, and leaves. As the plant dies and dries, the seeds hanging out in the sun and wind gradually become ready to disperse, while the desiccated plant material breaks down into mulch and cover for new life. The resulting complex seasonal landscape welcomes death into the centre of the garden as the foundation for new life to come up beneath it.”

Indigneous populations globally have carefully cultivated and developed their native seeds over generations in harmony with cycles of life and death, and are passed down from generation to generation. It is sad today how few of us know how to grow or cultivate a plant from seed, or how to instinctively think in these cycles, or to have an opportunity in our busy lives to plant our hands into the Earth.

As one of over 1000 documented species of native grasses in Australia, kangaroo grass has been a dominant crop for Indigenous and broader Australian agriculture for thousands of years and is one of the most widely distributed grasses in the country. Although kangaroo grass itself is not endangered as a species it does grow in Temperate Grassland communities – which have declined by over 90% in their extent and are listed as either endangered or critically endangered under the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act.

Part of the recultivation and revegetation of kangaroo grass allows us to shine light on the history and story of this plant. Bruce Pascoe, of Bururong, Yuin and Tasmanian heritage, conducted research for his seminal book ‘Dark Emu’ published in 2014 that showed the harvesting of grain in kangaroo grass was made into flour to make damper and porridge. This grain was especially relied on in arid areas and is a process that dates back at least 30,000 years, with grinding stones found in archaeological sites in Cuddie Springs and the Darling River. As Pascoe’s book ‘Dark Emu’ revealed, prior to European settlement, Australia had a wheat belt that covered a vast proportion of the country and sustained Indigenous nations with cultivated and prepared breads – who began these processes at least 20,000 years before others anywhere else in the world came up with the same kind of enterprise, invention and chemistry – making Indigenous Australians the first people on Earth to bake bread.

The whole plant had other uses too, the leaves and stems were also used to make cords and string, especially for fishing nets. Kangaroo grasses embody a long living history, not only with regard to sustainability and the future of food for Australia, but for reconnecting with culture through a return to what this land remembers and listening to the knowledge and wisdom of our First Nations people. Bruce Pascoe is today still leading the way as one of the central figures with Australian universities and the CSIRO in what is one of the most exciting environmental developments taking place in Australia. Growing and learning about our native plants helps recognise our Indigenous history and the misconceptions of the oldest living culture on Earth, that Aboriginal people were the first agriculturalists and engineers of this land, and we still have so much to learn.

Speaking over to environmental health, these grasses are perennials, so once the crop is established you don’t have to plough the land again with harmful tillage or add fertiliser or pesticides – and so the CO2 emissions are going to drop dramatically because you’re not turning the soil over and releasing carbon into the atmosphere. Dr Kate Howell, a biochemist of The University of Melbourne, says we should be cultivating native grains, not European grains, and that when you talk to people about this research, they have a certain fire in their eyes.

Vandaya Shiva, the Indian scholar, environmental activist, food sovereignty advocate, ecofeminist and anti-globalisation author writes and speaks on how all the pesticides and chemical fertilizers of today have ancestries in Zyklon B2 poison gases, with ancestries in explosive factories. Rachel Carson revealed this decades earlier in the pivotal novel ‘Silent Spring’ of 1962 on the use of pesticides, stating: “all my work has shown me again and again that the agrochemical industry is a war industry—it’s a continuation of the war industry, and it is engaged in war against the earth and its species. When we talk about the sixth mass extinction, we need to remember that we have designed these chemicals to exterminate, pushing some human beings and other species to extinction. It is because we’ve defined other species as our enemies, our competitors.”

Today, some 50% of greenhouse gases come from this oil-based, poison-based, globalised food system and reliances on nitrogen-based fertilizers. If we want to find our way out of this ecological crisis and sixth mass extinction then we have to make peace with the seed and, through the seed, make peace with the earth. Our native flora, including grasses such as kangaroo grass have evolved over thousands of years to grow harmoniously in Australian soil and climate, they generally thrive in low fertile soils that already exist and don’t require any fertilisers or practices of soil tillage that release CO2.

When we eat, there is consciousness of how the food was grown. Did it regenerate biodiversity or did it destroy it? When you realise the culture of seed saving is deep within all cultures, then conserving and saving seeds becomes a regeneration of cultural diversity; and biodiversity and cultural diversity cannot be separated. For Mexico it’s the culture of corn. For the cultures in India—they evolved 200,000 rice varieties—it’s the culture of rice. For Australia, there’s a culture of grains, cultivated for well over 30,000 years. With the fast emergence and corporate patents of GMO and hybrid seeds, where they are being privately protected under intellectual property laws – what is actually being seen is that some of the best innovation is being seen in the field, on Country, not in these labs. Local and native seeds have been shown to be outperforming these GMO varieties in various trials in extreme climatic conditions. This further tells us that these native grasses have naturally adapted over millennia for the tolerances required at this point in time we find ourselves.

It is important to mention here that what should be cultivated in this space are projects that are led by First Nations people, as Indigenous spaces that non-Indigenous people can actively get invited into and join forces via active partnerships.

As generations of these cultivated seeds lovingly persist as iterations of resilience, through their biological programming and co-evolution with the human experience – we can view seeds as the blueprints for sustainable and livable futures – with each seed a direct reflection of the investment that the previous generation packed into every endosperm. Writer Suzanne Pierre articulates this aptly in saying “seeds like people, would be woefully unprepared for the world ahead without the relationship that exists between the past and the present.”

Around the world what is concerning is that we are seeing private companies making it illegal to grow, save and exchange seeds – especially those for food. There are many seed activists, by farmers and other members of communities who are fighting to keep local native seeds in the hands of the many – because corporate control of these seeds become tools to extract profits, not feed and nurture people and restore biodiversity. To describe this with an expression from the global seed sovereignty movement: seed in the hands of the few is dependency; seed in the hands of the many is freedom.

Returning to the words of Suzanne Pierre: “seeds anticipate unwelcoming conditions, competition and a long journey before finding a safe haven.” Additionally, nature expects that not every seed will fall on fertile ground, which is a lesson in cultivating our personal attitudes to align them with life as it truly functions. While not every seed can fall on fertile ground, we can invest in a shared strategy for nourishment, for the seeds that may potentiate fertility.”

Whether you decide to go and plant all of your seeds, or choose to carry them around with you in your wallet, let them be a symbol of hope. Keeping seeds as a seed keeper, described by writer Owen Taylor, means there are ways to look at seeds as metaphors; the fact that we plant this one seed and sometimes we can receive a further thousand or tens of thousands of seeds from just one plant, really speaks to us about abundance and allows us to believe in abundance rather than continually succumbing to a scarcity mindset of lack and loss – one that only further digs us deeper into our current crisis.

Rowan White, the seedkeeper and founder of Sierra Seeds and the Indigenous Seedkeepers Network from the Mohawk community of Akwesasne says that “We are all indigenous to somewhere, and we’re all called in this time to be in inquiry about decolonizing ourselves and our relationships; and that process is multisensory. We can’t just think our way out of the predicament that we’re in. It really requires us to reimagine the way in which we engage with the world from a multitude of senses.”

It is time we step away from reductive perspectives of nature, and see the true value in all the abundances that surround us every single day in even the most urban places. As the world’s seeds are becoming increasingly locked into giant institutional ‘vaults’ and ‘banks’ catering to only an elite few, it is apparently clear where there is still so much work to be done. We don’t need museums to preserve varieties, we need everyday people to grow them.

When we ask ‘what does shifting power look like’, it wouldn’t be so far-fetched to sketch the silhouette of a seed, and a sprouting stem. Reestablishing native grasslands and the life they sustain, that in turn sustain and nourish us, all trace back to the generosity of a single seed.

Marg Grounds,

Indigenous Plant Consultant & Designer at Victorian Indigenous Nurseries Co-op (VINC)

Marg Grounds has worked in Horticulture for 16 years designing, installing, and managing multiple large-scale gardens (including the Abbotsford Convent).

Tait worked closely with Marg & VINC to bring the Recultivate installation to life with the specification, design and planting of Victorian Indigenous Grasses & flowering herbs.

Recultivate’s Plant Communities

Ecologists and botanists have examined plants in the field and can identify patterns of plant associations called ‘communities’. Revegetation managers refer to these communities when choosing species combinations, often aiming to recreate what was originally present at the site.

In specifying the Victorian Indigenous plant species for Recultivate, I have drawn from three key plant communities – Plains Grassland, Grassy Wetlands and Streambank Shrubland.

Plains Grassland

I chose the Plains Grassland community because it was once very extensive in the state of Victoria, and is now poorly reserved. Before European settlement, a lot of Victoria (including parts of Melbourne) was covered in grassland. Europeans saw these mostly flat plains with few trees as perfect for grazing sheep and cattle. The vast majority of the grasslands were destroyed by grazing and cultivation. Grasslands ran through what is now the northern and western suburbs of Melbourne. The suburbs are ever-expanding with industrial areas and freeways built, often directly destroying grasslands.

This plant community was dominated by Themeda triandra (Kangaroo Grass). Occasional trees, such as Eucalyptus camaldulensis (River Red Gum) and Allocasuarina verticillata (Drooping Sheoak) were found. We’re using the Plane trees (Platanus x acerifolia) in the courtyard of Collingwood Yards as a substitute for these larger species, and planting the smaller Banksia marginata (Silver Banksia) in Tait’s Xylem planters, which is another naturally uncommon tree species on the plains. Banksia marginata is a good choice for gardeners in inner Melbourne as trees rarely exceed five metres in height or width, and is bird-attracting.

As well as Kangaroo Grass, we are drawing on the diversity found naturally in grasslands to brighten up the installation. Native Bluebells (Wahlenbergia capillaris and W. stricta) are paired with white and yellow Hoary Sunray (Leucochrysum albicans) and Scaly Buttons (Leptorhynchos squamatus).

Native grasslands around Melbourne support a range of threatened species, including the Matted Flax-lily (Dianella amoena), Spiny Rice-flower (Pimelea spinescens), Button Wrinklewort (Rutidosis leptorrhynchoides), Golden Sun Moth, Growling Grass Frog, Striped Legless Lizard and the Grassland Earless Dragon.

Matted Flax-lily was assessed as critically endangered by the Department of Environment, Land, Water and Planning in 2020. Matted Flax-lily provides habitat for the native Blue-banded Bee. For further information on Matted Flax-lily see https://www.swifft.net.au. An example of steps taken to protect the species included Jukes Road Grassland. Managed by Merri Creek Management Committee in the City of Moreland, approximately 200 plants were translocated from the Craigieburn Bypass freeway project.

The Indigenous plants used in Recultivate to represent the Plains Grassland plant community include: Kangaroo Grass (Themeda triandra), Sheep’s Burr (Acaena echinata), Silver Banksia (Banksia marginata), Basalt Daisy (Brachyscome basaltica), Matted Flax-lily (Dianella amoena – critically endangered), Spur Goodenia (Goodenia paradoxa), Scaly Buttons (Leptorhynchos squamatus), Hoary Sunray (Leucochrysum albicans – endangered), Pussy tails (Ptilotus spathalatus), Button Wrinklewort (Rutidosis leptorhynchoides), Tufted Bluebell (Wahlenbergia capillaris), and Tall Bluebell (Wahlenbergia stricta).

Grassy wetlands

Another community I’m focusing on is Grassy Wetlands, which was seen as an impediment to agriculture and often drained to facilitate cropping and grazing. Wetlands provide critical habitat for birds, frogs, and insects. Gardeners can create a slice of the habitat with a few moisture tolerant plants, some rocks, and of course, water. Wetlands are highly diverse habitats and dominate on low lying areas (which are more likely to stay wet) and are often surrounded by Plains Grassland on drier ground.

The Indigenous plants used in Recultivate to represent the Grassy Wetland plant community include: Sheep’s Burr (Acaena echinata), Native Flax (Linum marginale), Swamp Everlasting (Xerochrysum palustre), and Tassel Sedge (Carex facicularis).

Streambank Shrublands

The final plant community I’ve chosen to represent in Tait’s Xylem planters is the Streambank Shrublands. This is the community that members of the public are most familiar with, they often contain walking tracks, and most councils conduct revegetation along creeks and rivers of the northern and western suburbs. These communities have almost totally disappeared, and intact examples are probably extinct in the region. A similar habitat was found around bogs and swamps, most of which have been drained for agricultural land.

Dominant species include the River Red Gum and Wattles and are typically found along creek lines in parts of Melbourne, including the Merri and the Maribyrnong River. The Plane trees at Collingwood Yards stand-in for the River Red Gum and Wattles. Underneath these taller species were a broad mix of plants. The middle layer consisted of tall shrubs of Bursaria spinosa (Sweet Bursaria), Melicytus dentatus (Tree Violet) and Leptospermum lanigerum (Woolly Tea-tree). We’ve chosen the latter as a representative to grow in Tait’s Xylem planters. We’re pairing that with Ficinia nodosa, a versatile species that suits pots or gardens and can tolerate dry periods once established.

The Indigenous plants used in Recultivate to represent the Streambank Shrubland plant community include: Woolly Tea-tree (Leptospermum lanigerum), Silver Banksia (Banksia marginata), Knobby Club-rush (Ficinia nodosa), Yellow Hakea (Hakea nodosa), Blue Bonnet (Hovea linearis), River Mint (Mentha australis), and Weeping Grass (Microlaena stipoides).

Featured Indigenous Grasses & Flowering Herbs

I’ve chosen to feature Matted Flax-lily, Kangaroo Grass, and Silver Banksia throughout Tait’s Xylem planters as part of Recultivate.

Matted Flax-lily (Dianella amoena) is a small plant and is a critically endangered species. I’ve chosen it because there aren’t many individuals of it left in the wild (certainly not in Melbourne), and it provides a habitat for the Blue Banded Bee.

Kangaroo grass (Themed triandra) was the dominant species in Victoria’s Plains Grassland plant community. You’ll see it a lot in remnants beside railway lines. The seed heads are very iconic, and the Victorian Indigenous Nurseries Co-op (VINC) uses Kangaroo Grass as its logo.

Silver Banksia (Banksia marginata) is a beautiful, architectural small tree suitable for suburban gardens. Silver Banksia will only reach about 5 meters high.

Preserving Indigenous Plant Communities

Revegetating public land and growing these plants in our gardens creates demand for the species and raises awareness of their plight. Species preservation is achieved by maintaining a broad gene pool of diversity. Victorian Indigenous Nurseries Co-op (VINC) collect new seed and cutting material annually. VINC grows plants to order for councils and other land managers, who in turn use these plants to revegetate reserves and parks in the suburbs. Members of the public are also welcome to purchase plants through VINC’s retail space.

People in general are coming to understand that nature created diversity and that planting trees is not enough. A suite of grasses, orchids, lilies, daisies and shrubs are also required. Often it helps to focus on a bird or butterfly species to bring home the complexity of habitat interactions.

Residents have a lot of options when it comes to assisting with preserving Indigenous plant communities. Even with a small garden they can grow some Indigenous plants in a pot. They could build a frog pond in their back or front yard: grab a few of the more moisture tolerant plants, put a few rocks around (and of course add some water), and you’ve got some frog habitat.

Residents can convert part of their garden to Indigenous plants. I recommend obtaining a copy of a Field Identification Guide, and becoming familiar with your local plants. Often, remnants of grasslands are mown through ignorance. Microlaena (along with several wallaby grass species), also make a suitable native lawn in Melbourne. Native lawns use less water and require no fertiliser.

Landscape Architects can include Indigenous plants in all (or part) of their designs, and promote information on the status of the species in the communities. If they can source plants from reputable Indigenous nurseries (there are many around the state), these nurseries are often non-profit organisations and are motivated to propagate plants for use in improving the environment. Landscape Architects could also move away from ordered gardens and landscapes. “Messy is good” is an adage often cited regarding habitat gardens. Rank grass is protection for skinks or frogs and fallen branches on the ground provide habitat for little insects like moths and bats. This all adds to the ecosystem.

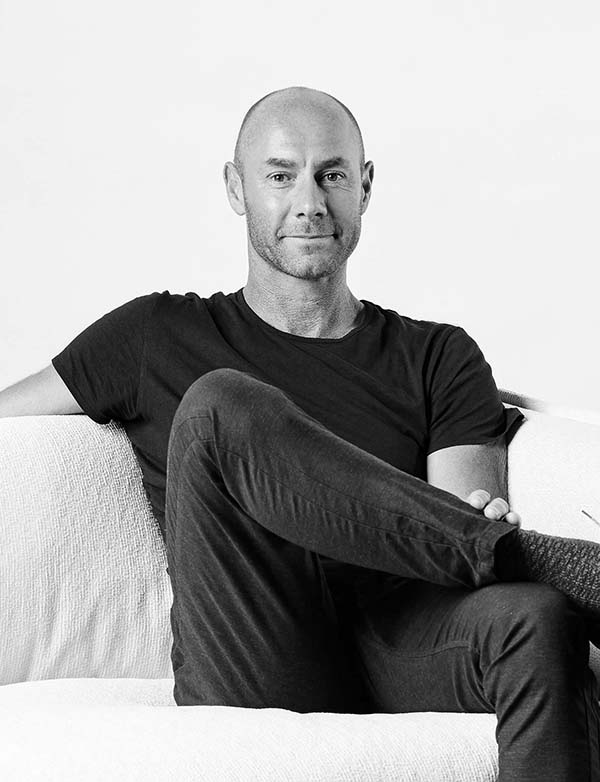

Adam Goodrum,

Designer of Xylem

As one of Australia’s most prominent industrial designers, Adam Goodrum has led an illustrious career having worked with the world’s biggest design houses including Louis Vuitton, Cappellini, Veuve Cliquot and Norman Copenhagen. Goodrum was awarded the NGV Rigg Prize, among other accolades.

The Design Concept Behind Xylem

Xylem was designed in response to the importance of biophilic design in workplaces, the urban realm, and educational spaces. The design leans heavily on its principles – ensuring people have access to fresh air, natural light, plants and nature-inspired spaces.

‘Xylem’ itself is a biological term referring to the branch-like vascular tissue in plants that transports nutrients from roots to leaves, and allows them to photosynthesise. Borrowing from this concept, the Xylem collection is a system that intimately connects people with the health-promoting benefits of plants – a reminder of our interconnectedness and dependence on nature. When the collection is configured into branch-like connections, it is also reminiscent of these vascular tissues.

Configuring the Xylem Collection

The singular drum element provides the base building block of the whole collection. It can be used as a planter, an ottoman, or it can be adjoined to a bench – from there the possibilities are endless. Xylem can branch out like a root system, form a cluster, become circular, or snake along in a single line for narrower spaces. Modules can be oriented to encourage people to come together (for socialisation or collaboration), or oriented to allow people more solitude (for focused work or breathing space). Additional components including armrests, backrests and side tables can also be added to further support users.

Singular Xylem Pods and Planters may also be used to form arranged clusters. Playful and inviting spaces can be created when clustered in various heights and diameters, allowing people to rest, work, or even dine informally. After the last two years of the pandemic, people have worked from home and from different environments. I think it’s always good to mix it up; I can see people working on their laptops sitting on the bench, or perhaps enjoying their coffee while they wait for public transport

Xylem’s chameleon-like design finds relevance across a myriad of applications. While predominantly designed for the workplace, urban realm, schools, universities, shopping centres and healthcare facilities, the collection can also be used in residential applications to incorporate informal seating and greenery. And, as we find ourselves looking to bring the “outdoors-in” more and more to enhance our relationship with nature, the collection is just as relevant indoors as it is outdoors.

Susan Tait,

Creative Director of Tait

As one part of Tait’s founding duo, Susan has been at the helm of Tait’s creative direction for 30 years.

The Tait Story

Tait began in a little factory in Fitzroy back in 1992. Gordon was a sheet metal craftsman and I was a Creative Textile Designer, and we began making one-off furniture pieces for people. Once we started to look around at what was available, we realised there wasn’t a lot of outdoor furniture made specifically to suit the harsh Australian environment. So we set out to design some of our own pieces, and it went on from there.

Over the last 30 years, we’ve continued to design and make outdoor furniture. We’ve continued to learn, hone, and improve our designs and the quality of our pieces. We have a team of around twenty-five makers and passionate craftspeople working at our Melbourne factory. We make 95% of our products here in Australia, and this is something we continue to be very proud of. We collaborate exclusively with Australian designers, and the Xylem collection marks the 5th collection we have produced with Adam Goodrum.

Xylem’s Colour Inspiration

As for all of Tait’s collections, the colours we have chosen for Xylem are taken directly from the Australian landscape. We have chosen soft, weathered colours. The earthy reds and ochres of our rocky outcrops; soothing greens taken from our Eucalyptus forests; and paperbark, sands, and deep ocean blues reflecting our coastlines. The light and rich colours are so unique to Australia, and this understanding helps to ground the design in its environment. Designers can choose from an array of powder coat colours to ensure Xylem compliments and works cohesively with their project.

Being out in the Australian landscape is a very important part of my design process. The landscape is a constant source of inspiration to me. My office pinboard is covered in pictures of Australian landscapes and Australian native flowers. My shelves are filled with rocks, shells, strips of bark, drying gum leaves – all sources for new colours.

During the pandemic, my bushwalks were closer to home, but even along the creek (near my house), there were so many beautiful Australian natives, Wattle, Banksia and birdlife. My latest nature collection has focused on seed pods. There are a couple of beautiful gum trees at the front of our factory in Thomastown (which is quite an industrial area). I’ll often wander out to the nature strip and check out what bits of bark and leaf and seed pods I can find on the ground there and drag them back into my office for inspiration.

All these offerings from nature are beautifully weathered; they’re lovely to hold, look at, and be with. I like to think that that’s a bit like experiencing a piece of Tait furniture outside. That it’s a comfort, somewhere to enjoy, either by yourself or with friends and family.

Gordon Tait,

Founding Director of Tait

Originally a sheet metal craftsman, Gordon Tait is the manufacturing prowess behind Tait’s Australian designed and made outdoor products.

The Making of Xylem

Xylem marks the 5th collection Tait has made with Adam Goodrum. Working across many typologies, Adam comes to the table with a vast knowledge of materials and processes. Coupled with Tait’s 30 year’s experience in manufacturing outdoor products, we’ve been able to develop a powerful design and manufacturing partnership. It’s always fun, and its always a pleasure to work with Adam, we’ve become like family.

The materials we’ve employed in manufacturing Xylem include; anti-corrosive aluminium, glass-reinforced concrete and sustainably sourced FSC® Spotted Gum timber. We’ve utilised these materials across a number of our collections (with great success for many years) due to their high-performance in Australia’s harsh elements. Xylem’s Aluminium elements are formed by folding, making them extremely strong and durable, and the Xylem Pod’s timber seat is crafted with smooth, curved edges providing a comfortable place to sit.

The glass-reinforced concrete base for both Pod and Planter is perhaps one of the most distinctive design features of the collection. It provides superior durability and ample weight, making it ideal to withstand use in public, high-traffic and wind-prone sites. Internally, the GRC base also becomes a waterproof reservoir to retain water, with an additional self-watering wicking system available (aiding plant watering greatly). The raw concrete element of both Pod and Planter also provides a fresh contrast against Tait’s richly hued, textured powder coat colours.

Introducing Xylem by

Adam Goodrum for Tait

A modular planting & seating system which forms a conduit between plants and people.

Launching April, 2022. Subscribe below to be notified of the Xylem collections release.

Presented by

In partnership with

VICTORIAN INDIGENOUS NURSERIES CO-OP

Tait acknowledges the Traditional Owners of the land on which we work, and pay respects to Elders past, present and emerging.

Instagram

Facebook

Pinterest

Vimeo

Linkedin

This installation is part of Melbourne Design Week 2022, an initiative of the Victorian Government in collaboration with the NGV.